Life behind China’s Great Firewall

We’ve all had it happen: You’re surfing the Internet at work, or maybe the library, and you try to get to a site somebody doesn’t want you looking at. Blocked. Access denied. You are stopped by an invisible firewall that stands between you and the information you’re seeking. It’s frustrating, isn’t it? Now imagine if this invisible firewall existed beyond the computer.

Now stop imagining, because, in many countries, this is reality.

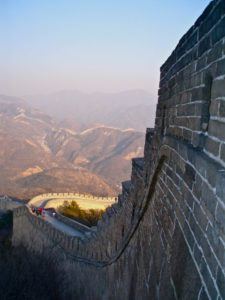

China may be the most famous country to have erected a firewall around itself and its people to keep certain ideas and information out. They call it the “Great Firewall,” and it is not confined solely to the cyber world. Under communist rule, China has implemented measures to hide or otherwise gloss over things it deems inappropriate or dangerous; things it does not want the average Chinese citizen to think about.

China may be the most famous country to have erected a firewall around itself and its people to keep certain ideas and information out. They call it the “Great Firewall,” and it is not confined solely to the cyber world. Under communist rule, China has implemented measures to hide or otherwise gloss over things it deems inappropriate or dangerous; things it does not want the average Chinese citizen to think about.

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about this specific breed of government-decreed censorship, thanks to reading about Google’s battle to retain operation of its search engine in China while refusing to censor its search results any longer.

In the past, Google — along with any other search provider in China — had to edit its results in line with the stance of the Chinese government. In January, however, Google was contemplating pulling out of China because it no longer wanted to censor itself. An outcry by Chinese users persuaded it to stay, but Google decided to go rogue and started directing all searches from mainland China to its unfiltered Hong Kong site.

The Chinese government was not happy about this, and threatened to suspend Google’s Internet license. A compromise was eventually reached: Google went back to its old filtered search engine, but now gives users the option to click a button to be taken to the Hong Kong site. However, Beijing’s controls could still block banned results from showing up in searches in mainland China, even through the Hong Kong site.

Crazy, right? At least, it seems that way to me, an American who has the freedom to search for anything on the Internet and get a variety of results that aren't pre-approved by my government. But that’s communism for you. China utilizes its “Great Firewall” to block access to materials it views as “subversive or pornographic.”

And, surprisingly, for the most part, people in China accept this.

I visited Beijing and Shanghai briefly in 2007 as part of a large tour group (my college marching band). China surprised me in a lot of ways, but one thing that stuck with me (and made me slightly uncomfortable at the time) was this whole topic of government censorship and the “Great Firewall.”

We were on a tour bus, crawling through the Beijing traffic on our way to the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square. As an American, I am aware of what happened there in 1989 — events often referred to as the Tiananmen Square Massacre. Anywhere from 241 to 10,000 people died in military violence, depending on who you ask (China says 241, NATO says 7,000, the Soviets at the time said 10,000). But, in China, this event is simply referred to as the “June Fourth Incident.” Media and websites are forbidden to mention it, and photos and video footage from inside the actual square on that day are virtually nonexistent. According to the Chinese government, it didn’t happen.

We were on a tour bus, crawling through the Beijing traffic on our way to the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square. As an American, I am aware of what happened there in 1989 — events often referred to as the Tiananmen Square Massacre. Anywhere from 241 to 10,000 people died in military violence, depending on who you ask (China says 241, NATO says 7,000, the Soviets at the time said 10,000). But, in China, this event is simply referred to as the “June Fourth Incident.” Media and websites are forbidden to mention it, and photos and video footage from inside the actual square on that day are virtually nonexistent. According to the Chinese government, it didn’t happen.

As our Beijing tour guide — a bubbly, twenty-something Chinese woman from rural northern China — talked to us about Tiananmen Square, she acknowledged this void of information. She told us that she could search phrases related to the incident on the Internet and get no results. She told us that she — like many Chinese people her age — is aware that something happened in Tiananmen Square in 1989. But she doesn’t know what, and she isn’t sure if anyone was hurt.

All of us on that bus knew that we, as Americans, could go home and type in the same search and get over 1.2 million uncensored results. We knew that we could find out that thousands of people were hurt and killed in 1989. But, whether out of fear (we've all heard stories about Chinese prisons), sheer bafflement, or pity, none of us could bring ourselves to tell any of this to her. And she never asked.

I often wonder: What kind of implications does the “Great Firewall” really have on China? Is it detrimental to a country and its people to withhold certain information — information about their own history, no less — from them? If they knew what was being kept hidden behind that firewall, would they still love their country as much?

I often wonder: What kind of implications does the “Great Firewall” really have on China? Is it detrimental to a country and its people to withhold certain information — information about their own history, no less — from them? If they knew what was being kept hidden behind that firewall, would they still love their country as much?

Somehow, I think they might. There’s a different mindset in China. People don’t seem to resent communism. In fact, many that I met in my short time there were thankful for their jobs and the way the government takes care of them and their cities. Perhaps it’s just blind patriotism and ignorance. But perhaps it’s not. Perhaps I just have completely different views because of where I grew up — here in the U.S., where we’re obsessive about our freedoms.

Recently, I met a young Chinese man who is enamored with America and its history. He knows all 50 states, and the date that we signed our Declaration of Independence. He was astounded when my dad explained to him that anyone in the U.S. who isn’t a criminal can legally buy a gun. He invited me to visit him in Shanghai, and requested that I bring American history books along with me.

I wonder if he has ever read an American history book. I wonder how they compare to the government-approved history books that I’m sure he read in China as a student. I wonder, if I tried to mail him these books, whether he would even receive them, or if they would simply “disappear” somewhere along they way.

Just thinking about all this makes me even more contemplative. And confused. And maybe even a bit angry. But then I have to remind myself that I am an American, and that I don’t know nearly as much as I think I do. I have no right to judge. I can only learn, and ponder, and hope that I never have to know what it’s like to live behind a Great Firewall.

Comments

Post a Comment